It’s been a marvelous Spring in Washington DC. We’ve avoided creating a global economic catastrophe. They tell us the month of May was “one of the nicest in memory.” (It was!) And now, it’s June, which means we’re mere weeks away from the one year anniversary of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), and that means some reflections are in order.

As longtime readers of FLT will know, the UFLPA is a paradox. As I wrote last month, it is the marquis law governing the intersection of business conduct and respect for human rights, and yet is a technical catastrophe. I remain staunch in my view that the primary ailment of the UFLPA is the absence of any serious policy discussion around what a forced labor import ban is and should be.

At some point, lawmakers and policymakers in Washington must have that discussion. When they do, it should result in an updated legal structure that defines with greater specificity how the most important factual and legal determinations governing enforcement will be made. In turn, that will not only enable the U.S. forced labor import ban to modernize (something long overdue) but also cause the law to take its proper role within the rules based international order. That role is somewhere near the top. It’ll be a crowning achievement.

We’ll know we’ve reached that goal, because the law will incentivize all actors within the ecosystem (importing corporations, producing corporations, workers, activists, and border enforcers) to play their unique roles in helping bring about the identification and eradication of forced labor. That end goal is not achievable by any one of these constituencies standing alone. It requires them to work in harmony, or sometimes, in contraposition to one another.

We cannot suppose that getting all parties to profess agreement with the goal is enough to ensure it will be achieved. If self-aggrandizing declarations of allegiance to ethical supply chains is all that was needed to end the scourge of forced labor, we’d have achieved it long ago. But they’re not, and so we haven’t. Incentives, economic and otherwise, are what guide all behavior. The law has a unique role to play in shaping those incentives, and that is why an updated legal structure—eventually—is a necessity.

But for now, we have the UFLPA. An aggressively-funded, vigorously-enforced law where self-aggrandizing declarations of moral excellence are not just useless, they’re disfavored. For the first time, actually proving things about your supply chain—to a thoughtfully skeptical government regulator—is what matters. That is no small achievement.

I’ve been known to show CBP some tough love in these pages, but on this anniversary of the UFLPA, I’d just like to honor them for their irreplaceable role. CBP plays an unqualifiedly critical role within the ecosystem. Having a border enforcer that wants to study traceability packages en masse and decide whether it they contain credible depictions of actual supply chains is an indispensable piece of a functioning forced labor import ban.

The world needs a regulator that doesn’t just swallow every allegation of forced labor lobbed into the ether by a fire-breathing activist. We have that in CBP. Just as importantly, the world needs a regulator who doesn’t trust a self-aggrandizing corporate declaration of moral excellence any further than they can throw it. We have that as well. We need regulators who expect proof, who work to understand the proof they’re presented, and make fair, reasonable decisions based on record evidence. CBP: I’m pretty sure folks don’t thank you enough for what you do, so today I do.

CBP deserves special commendation, in my view, because the enforcement regime they’ve managed to build over the first year of the UFLPA has been built without the benefit of a governing statute. Truly! They were handed nothing! The UFLPA was drafted without contemplation of the fact that it might be hard to know, in advance, which shipments contain content from Xinjiang or a UFLPA Listed Entity. CBP invented the “applicability review” to solve this problem. There is no statute governing such reviews, or setting forth an applicable standard of review, let alone guidance for how CBP officials should go about conducting the reviews. That this mechanism was created at all was an impressive feat of agility for one of the federal government’s oldest agencies.

And so, as I turn to the thesis of this particular post, I’d like to speak to whomever it is at CBP that can claim intellectual ownership of the “applicability review”. I imagine there is a small cadre of dedicated civil servants, probably a few leaders of the forced labor division or TRLED, and some of their most trusted attorney advisors, who have taken the time to concern themselves with the question of how this is all supposed to work. Because, while the one-year anniversary of the UFLPA is an opportunity for celebration, it’s also an opportunity to consider how enforcement should mature over the coming year. All good things need to grow, and for the UFLPA, I have a few ideas.

In this post, though, I’ll leave you with just one big idea, and I’ll use a military metaphor to make the point.

As any army general would tell you, it’s impossible to ensure military supremacy without having individual soldiers trained to win battles in hand-to-hand combat. This is why all military training begins with fundamental recruiting standards of physical fitness and training. It’s why boot camp is a thing! But at the same time, no modern military expects to win an conflict by deploying a battalion of warriors to conduct hand-to-hand combat against an equivalent (let alone larger) number of adversaries.

And yet, this is the situation CBP finds itself in. It has been granted a military-caliber budget (ok, fine, shrunken to the scale of trade enforcement funding, but still) and its arsenal of import specialists are engaged in hand-to-hand combat against individual shipments. One entry at a time. One container at a time. One traceability package at a time. The mission: find and exclude products with supply chain links to Xinjiang or a UFLPA Listed Entity. CBP commanders must demand that their teams of import specialists engaged in this work comply with rigorous standards of intellectual fitness and training. That much is a given. But for the love of all that’s good and holy, please don’t try to win this war by commanding your foot soldiers to throw their bodies into the breach!

For better or for worse, that is how CBP is conducting UFLPA enforcement presently. (And, statistics show, it’s mostly for worse. More on that below.) Once it settles on a target for enforcement, CBP just detains entry after entry, shipment after shipment, container after container, demanding production of full traceability package after full traceability package. Every PO, invoice, bill of lading, proof of payment, trucking receipt, warehouse receipt, production record, you name it, all linkable back to a specific SKU and shipment. Rinse and repeat.

What should CBP be doing instead? What is A Better Way To UFLPA™?

CBP should be undertaking to have strategic conversations with the targets of enforcement (i.e., the importer and targeted tier one manufacturer), for the purpose of ensuring that the hand-to-hand combat (i.e., the review of specific traceability packages for specific entries by teams of CBP import specialists) delivers maximum value to CBP’s enforcement objectives for the UFLPA. That isn’t happening today, but it could.

Let’s consider solar detentions as an example, because understanding that the method of current UFLPA enforcement is not only directly contrary to achieving the country’s carbon emissions goals but may also contribute to our demise as a species could help focus the mind.

If CBP picks a target for enforcement, say, a Chinese-owned, Malaysia-located manufacturer of solar panels, it should be open to engaging in a higher level strategic dialogue with that manufacturer and/or the associated importer, around which supply chains that manufacturer is leaning on to supply the U.S. market. It should be open to having the conversation in advance. Suppose the manufacturer is looking to supply the U.S. market with product manufactured from U.S. polysilicon? This is merchandise that would, prima facie, not be subject to the UFLPA on a polysilicon basis.

There are a lot of ways CBP could handle these imports. It could follow the current approach and detain dozens or hundreds of entries, and require the importer to produce a comprehensive traceability package for every one, until it reaches some undefined degree of satisfaction, and decides to move the enforcement storm on to another target. Or, it could have a conversation at a higher level.

For example, CBP might ask the importer to declare the supply chain(s) that will exist behind all imports over a particular span of time, say six months, or a year. It could give the importer time to examine the supply chains, figure out what will be coming to the U.S. over that span, and then make a binding legal representation to CBP regarding what CBP will find if it chooses to spot check traceability materials for any given entry during that span. A successful spot check detention (i.e., one that matched the importer’s binding declaration) would allow the merchandise to keep flowing unabated. A failed spot check detention might trigger a reversion to the conventional enforcement approach.

This just one possible scenario. Countless others abound. For products where the upstream supply chain of a given tier 1 manufacturer exhibit a high degree of variability from entry to entry, a comparable question might be posed. CBP might ask the importer to declare the full panoply of upstream supply chain entities that will be utilized over a given span of time, and CBP could spot check the veracity of such a claim. Any detained entry within the span would have to reflect in the traceability package a permutation of the declared upstream entities. If that permutation of entities is as advertised, trade keeps flowing. If it deviates, consequences flow instead.

The point is not that CBP should relinquish entry-specific reviews, or stop demanding actual proof of the constitution of the supply chain. Far form it! Those are among the only real powers CBP wields. Rather, the point is that because CBP has the power to demand and evaluate these kinds of document production—because it has warriors trained for such combat—it should consider how to leverage that capacity to convene higher-order conversations with importers and manufacturers, deploying the traceability demand in more targeted instances, and allowing such traceability reviews to carry more precedential effect, whether positive or negative. This would be a different way to UFLPA, and a better one.

If you’re wondering why this matters (and why I’m burning precious FLT fuel exhorting CBP to develop a more strategic approach to enforcement), it’s because CBP’s own detention statistics show that overwhelmingly, CBP is stopping merchandise under the UFLPA that is not subject to the UFLPA.

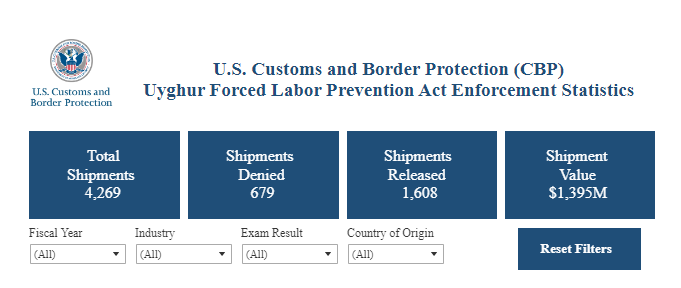

Here’s the link, and here’s the latest screenshot:

CBP has reached a decision on 2,287 detained shipments to date. Of these, more than 70% were found not to have a supply chain link to Xinjiang.

The 1,608 released shipments represent hundreds of millions of dollars of trade that was blocked and delayed when it should not have been. It also represents, conservatively, tens of thousands of hours of CBP review time spent on analyzing the supply chains of ultimately compliant merchandise. Bodies into the breach, indeed.

The point is, for most of these shipments, the importers likely already knew, and maybe even already had proof that the supply chains in question did not link to Xinjiang. Or if they didn’t, they certainly were capable of collecting and producing such proof upon demand. It would be a small but significant step for CBP to begin asking that question in advance, in the context of a structure where an importer can provide declare an answer that carries consequences. If documented as true, then follows the ability to import unencumbered. If unsupported by proof, then follows a consequence of appropriate magnitude (e.g., a reversion to full detention treatment).

CBP’s lawyers may fear that the agency cannot have this kind of dialogue outside the context of any individual importation. Individual importations, after all, are the jurisdictional nexus through which CBP is able to regulate commercial activity.

My response to this concern would be that CBP could initiate the dialogue in the context of an individual detention, or series of detentions. It might even limit the option to importers that are “trusted traders”, or manufacturers that are CTPAT participants. In any event, no substantive or procedural decision in a UFLPA applicability review is currently governed by statute, so this proposed “higher order” approach to enforcement wouldn’t require CBP to break any new ground on that front.

Given that CBP’s own statistics show it is overwhelmingly detaining merchandise under the UFLPA that is not subject to the UFLPA, there is a strong legal imperative—and indeed, an equally strong organizational imperative—to figure out how to ensure enforcement resources are more judiciously deployed. This will require creativity, and strategic planning in the fight against forced labor. But for sure, the generals directing CBP’s forced labor trade enforcement are capable of both.