This week, I explore the relationship between CBP and the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, and the roles they each have with respect to forced labor enforcement. I explore what we can decipher from their respective histories, and what we can infer from recent actions.

In the early days of CBP’s forced labor trade enforcement, it’s fair to say there were some fits and starts. But however wild and wooly you may think forced labor enforcement is today, let me assure you. We’ve come a long way baby!

In 2016, mere days after The Loophole in Section 307 was closed, creating what we know today as the blanket forced labor import ban, CBP busted out the saloon doors rootin-tootin. It was quiet on those there streets—dead quiet—but CBP came out shooting.

For 22 years, CBP hadn’t issued a single withhold release order. You could probably count on one hand the number of CBP officials that even knew what Section 307 was. But it only took CBP 33 days and one leap day from when the Loophole was closed until the first WRO was fired off at a Chinese factory for using forced labor in making three different products.

At that point in my legal career, I hadn’t exactly done a lot of any work for Chinese companies. In the years since, I still haven’t. And yet somehow, that poor Chinese factory’s first appeal of the first WRO landed on my desk.

Seeing as no one at that time could credibly claim to be a WRO expert, there was a lot of learning to do, and a lot of explaining about what exactly had happened. One thing confounded us, however. My client was named in the WRO, on CBP’s “reasonable suspicion” that it had produced three different products with forced labor. The only problem? My client, in addition to insisting it had never used any forced labor, insisted that it simply had never even been in the business of producing 2 of the 3 products listed in the WRO.

We did a lot of due diligence on that, and as far as we were ever able to determine, the claim held up. CBP had come out of the gate guns blazing, and had misfired in a pretty significant way. (To CBP’s credit, it ultimately recognized its error, and rescinded the order.)

In those early days, a lot of people wanted a lot of things from CBP for forced labor enforcement, and it’s fair to say not everyone was satisfied. There were Democratic senators demanding that CBP get to egg-cracking and omelette-making. There were NGOs publishing damning exposes on forced labor in different industries, and wondering where the enforcement was.

Sometimes enforcement wouldn’t come at all. And sometimes it would come, just awkwardly late, and weirdly specific.

For example, in May 2018, Greenpeace published a gut-wrenching account of forced labor on a specific Taiwanese fishing vessel, Tunago 61. Almost a year later, in March 2019, CBP issued a WRO. On Tunago 61! Which seems kind of amazing until you realize that the report, as written up by Greenpeace, detailed horrific physical and emotional abuse dating to 2015 and 2016, which had led the crew of the Tunago 61 to revolt against their tormentor, the captain of the ship. By the time Greenpeace published its account, the crew had already been arrested for their retaliation, and were facing trial for murder. CBP quietly revoked the WRO on Tunago 61 in early 2020.

It was around this time that the idea for the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force (FLETF or the “Task Force”) was conceived. FLETF was created by an Act of Congress in December 2020—the bill implementing Trump’s renegotiated NAFTA, as it happens—and was instructed to provide some oversight and strategic guidance to CBP on forced labor enforcement.

Formally, the Task Force was charged “to monitor United States enforcement of the prohibition under section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 U.S.C. 1307).” Informally, it was charged with being the adults in the room.

Now, if that seems a bit harsh, or even malign . . . that’s because it kind of is! All of the specific tasks assigned to the Task Force could just as easily have been assigned to CBP directly. These included things like setting timelines to respond to petitions for WROs, and issuing biannual reports on the Section 307 enforcement activity that were to include the number of times goods actually got blocked, and what type of goods they were. Why Congress decided that a Task Force was needed, I can’t rightly say.

What exactly is the acceptable shape of a learning curve for an agency charged with enforcing the most powerful idea for a human rights law in history? How quickly should an agency be able to climb that curve when it has no dedicated budget to do so?

I can’t say if CBP’s growth in forced labor enforcement was ahead of, behind, or right on target. And by the same token, pulling the USTR and the Secretary of Labor into an advisory capacity on the questions of forced labor enforcement that could impact bilateral trade relationships seems kinda smart! In other words, I’m agnostic on the creation of FLETF. But I’m not so sure CBP is. Hence this week’s title.

When originally created, the Task Force had no actual responsibilities that would directly interlink with enforcement actions. FLETF was conceived to be a modest confab that would help map out some timelines, issue the occasional report, and be answerable to the relevant congressional committees. A nice gig for the designated deputy assistant secretary!

That all changed with the enactment of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA). At the end of the sausage-making fest that yielded the UFLPA, the TAsk Force had been charged with real work! Tracking down information—some of it fairly obscure—and publishing lists of Chinese entities known to the U.S. government to be complicit in forced Uyghur labor. It had to compile 4 lists (with around 23-25 individual bases for potential listing), and maintain them on an ongoing basis, interface with dozens of hungry NGOs eager to petition for listing, and evaluate what will almost certainly be hotly contested petitions for removal. Without a budget!

As I’ve written previously, Congress effectively created the first ever sanctions regime in the context of import trade, and ended up (intentionally or not) stacking it on the shoulders of a Task Force with, last I checked, no supporting staff.

The Entity Listing process is so central to the UFLPA, it came as quite a surprise to many in industry to discover that CBP isn’t actually limited to enforcing against companies on the UFLPA Entity List. Sure FLETF can list a Chinese company under the UFLPA. But did you know that CBP can enforce directly against its own target list of entities, and it’s free to pick from Chinese or non-Chinese companies when it does so? It can. I refer again to the CBP’s Shadow List, that I’ve written about previously. Anything FLETF can do, CBP can do . . . more.

Last week brought news of another. Under the UFLPA, there are “high-priority sectors” for enforcement purposes. Congress set out the first few by statute—cotton, polysilicon and tomatoes—and assigned to FLETF the statutory authority for adding additional high-priority sectors as it sees fit. Can you guess where this is going?

Two weeks ago, my colleague-at-large and fellow UFLPA guru Richard Mojica broke the news that CBP has updated the template documents it distributes with UFLPA detentions and is now demanding the production of detailed traceability documents for aluminum, in addition to the 3 already established high-priority sectors. There are a lot of unknowns about what this means. I asked CBP directly for a formal comment or copy of the document, and they showed me their badges and told me it was a secret. (Not kidding. Well, kidding about flashing their badges. Not about the secret part.) Richard’s client advisory is worth a read.

It’s certainly possible that there isn’t even a hint of intra-governmental competition at play here. For all we know, the Task Force and CBP might be working hand-in-glove on enforcement. At some point, FLETF will list more entities, and it may designate more high-priority sectors. It will be interesting to see if Congress ever expresses an interest in funding it. But no matter what fate awaits Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, this town is only big enough for one forced labor trade enforcer, and I think CBP would like you to remember who it is.

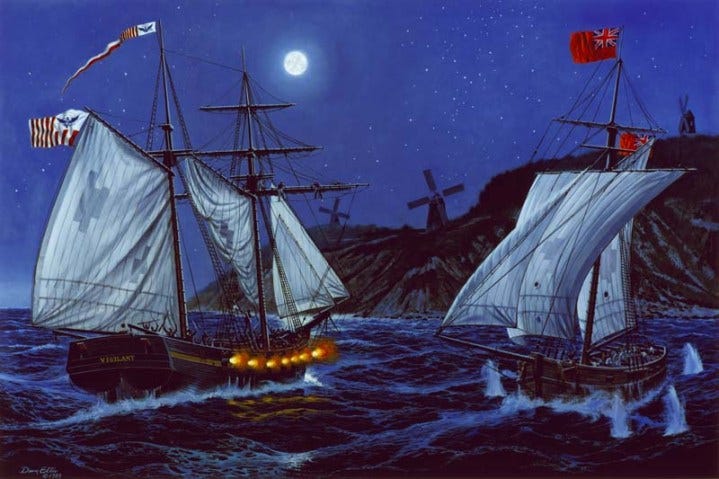

It’s worth remembering that U.S. customs has been a guns-and-badges law enforcement agency since the dawn of the Republic. A former colleague of mine (himself a former senior customs official) had a painting hanging in his office that I walked past probably 50 times before taking time to notice.

It was a painting of a “revenue cutter” which was a ship sailed by the U.S. customs service during the days when collecting customs duties was the only source of funding for the government. In the painting, it is shown having been drawn into service during the war of 1812, firing upon a British privateer known as the Dart, which had been threatening American merchant ships.

It’s just a revenue cutter, you might think. They’re only patrolling to collect taxes, you might suppose. 💥💥💥

Love this update, John. Another song came to mind courtesy of a proud son of NJ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nAxzn0--Oc