I had the privilege of speaking at a pair of industry events this week (in Washington and New York) on the topic of forced labor trade enforcement. In the process, I had the opportunity to hear from, and dialogue with, an array of current and former U.S. government officials with responsibility for forced labor trade enforcement.

While not every twist and turn from these events needs to be catalogued on the pages of FLT, I’ll admit I am a sucker for good public discourse. If you can get folks out from behind the computer screen, and away from scripted remarks, you can get a sense of who they are as people, and how they’re approaching their work.

If you care, and you’re willing to ask the question, you might even learn something really cool. Like, you might learn what I learned this week from the head of U.S. forced labor trade enforcement: the top three pieces of advice he would give to his counterparts, who will be building out and heading up forced labor trade enforcement in Mexico, Canada, or Europe. That can be worth far more than the price of admission.

This week, three particular exchanges stood out to me as worth the attention of FLT readers.

The first came as I again spoke with Brian Hoxie, director of the forced labor division in the Office of Trade at U.S. Customs and Border Protection, at an import compliance event hosted by ACI. Brian is the senior-most CBP official with exclusive subject matter responsibility for forced labor trade enforcement.

I actually spoke alongside Brian during the China Forum last month. (I’m trying to collect all five, to get the free t-shirt.) During that event, a comment Brian made stuck with me long after I walked out. Because I was moderating the panel this week, I had the opportunity to ask him a follow-up question about it.

Brian had said that when it comes to forced labor trade enforcement, CBP is “focused on entities, more than it is focused on goods”. That struck me as a curious assertion for a few reasons.

For one, the forced labor import ban is a decidedly goods-focused law. After all, it is the “goods, wares, articles, and merchandise” made wholly or in part with forced labor that are prohibited from importation. And with the exception of the UFLPA Entity List (which isn’t what Brian was referring to), the law doesn’t ban the importation of goods from specific entities. True, under the forced labor import ban, CBP can target specific manufacturers with enforcement actions like WROs and Findings, but CBP has generated worldwide attention precisely for its ambition not to use WROs in that way, choosing instead to target whole categories of goods and materials from broader geographic designations (e.g., cotton from Xinjiang or tobacco from Malawi).

I wanted to ask Brian what he meant in making that assertion, because, if CBP isn’t really focusing on the goods, who is?! I should note, Brian is not the only U.S. government official to make this assertion. Other senior administration officials have made a similar point previously (and I took issue with it then as well).

Brian’s answer was essentially that CBP is focused on entities because it has to be. If CBP is going to enforce the law against obscure sources of Xinjiang content, then pragmatically, it has to focus on which entities are most likely to making and shipping goods with such content to the United States. In other words: there really is no other way to do it.

I take that answer at face value. And rather than critique it for a second time, I’ll make a different point.

If you’re a policymaker attentive to the question of the forced labor import ban …

… you really ought to ask yourself: what is a forced labor import ban?

In trade, a law that focuses on targeted entities, and tries to block transactions with such entities is a sanctions law. A forced labor import ban is not a sanctions law. Or at least, it shouldn’t be.

Rather, a forced labor import ban is condition on market access. It asserts quite simply, that if you’re a party that has an interest in shipping goods across an international border and into a consumer market, there are certain instances (say, upon a credible concern about forced labor) that you’re going to have prove something about the supply chain, and/or the condition of labor used to make the affected goods. And no matter where you sit within the supply chain destined for that consumer market, a forced labor import ban creates the structural incentive for all parties to row in the same direction by collecting and producing relevant information.

A sanctions regime is, by design, a blunt instrument. We sanction bad actors, because we want to crush them economically. That is the goal. And while forced labor is perpetrated by bad actors, there can be many downstream parties throughout the supply chain with radically varying degrees of awareness of the tainted content, up to and including very good actors. Or at least, well-intentioned actors who are blissfully unaware of their complicity.

A forced labor import ban is, by design, a precise instrument. Or, at least, it should be. More on this another time.

The second noteworthy exchange came in a “fireside chat” with DHS Under Secretary for Strategy Policy and Plans, Robert Silvers. Robert does a lot of fireside chatting, including two on the same day this week in New York City! The one I attended was at Altana’s Directions Summit, which happens to hold the designation of poshest conference I can remember attending. Love Altana.

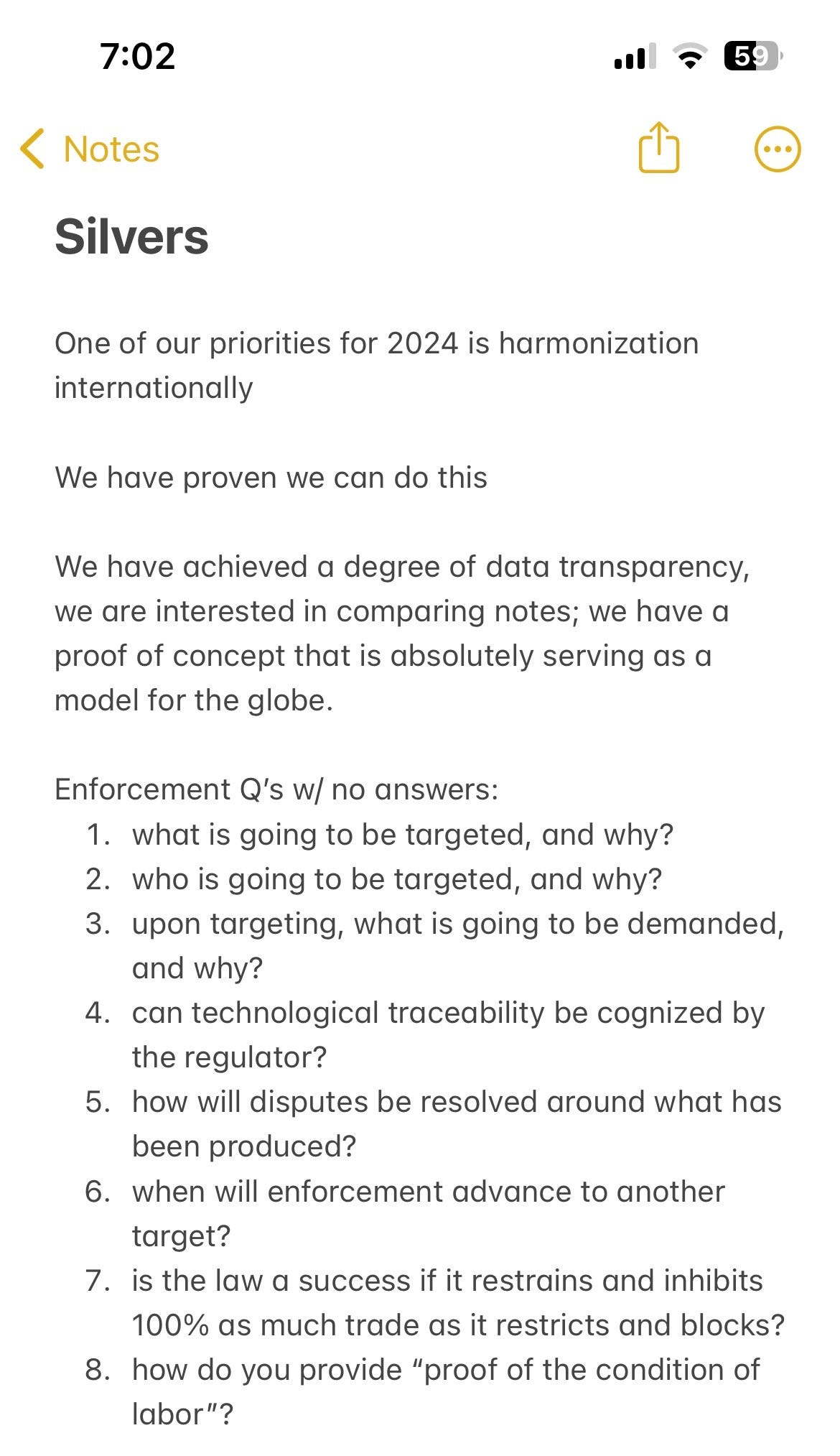

Robert delivered his fireside chat sadly without an actual fire, or even hearth, to provide an update on the work of DHS, including setting expectations on Entity Listing, and describing goals for UFLPA enforcement in coming months. But when he got to describing UFLPA priorities for 2024, and explained that 2024 will be the year of working to harmonize international enforcement of laws similar to the UFLPA, I nearly choked on my wasabi peas and Saratoga sparkling mineral water. (Told you it was posh!)

Harmonize? Internationally? How can you harmonize international activity without a clear set of rules that define what you’re doing and not doing? After regaining my composure, I grabbed my phone to jot down more of what he said, and then, reflexively, started tapping out a list of some of the most fundamental questions that cannot currently be answered according to any clearly defined rule approximating a law. Just the first eight that came to mind.

Ok, deep breath & level set. Harmonizing approaches to ban the importation of goods made wholly or in part with forced labor is a good idea. It’s a really good idea. Louisa Greve, Director of Global Advocacy for the Uyghur Human Rights Project made this point at the China Forum last month. And she’s right. No single consumer market, acting alone, could effectuate the ultimate desired impact on supply chain links to forced Uyghur labor. It’s going to require coordination.

I actually do hope DHS will convene conversations with its international counterparts in the coming year. It’s never premature to have conversations about cooperating! Heck, if my spicy commentary hasn’t proved too odious, I’d even hope to be invited to join as an industry participant. But just as in music, you can’t harmonize with something that has no defined pitch, in trade, you can’t harmonize something that has no rules. Maybe some good tough questions from the Europeans, Canadians and Mexicans would help focus the mind.

If anyone is confused about whether the U.S. “proof of concept” that is UFLPA enforcement has yet reached the status of a “rules-based approach ripe for harmonization”, I’d propose the following rule of thumb. Can an interested party understand how all the basic decisions are being made? Or any of them? And can an aggrieved party get a decision in writing that justifies the decision made in reference to a written rule?

Considering they were handed almost no structure from the UFLPA statute itself, the truth is, CBP and DHS have built an impressive enforcement apparatus over the last two years. Former CBP official Ana Hinojosa said during the Altana Summit she thinks CBP doesn’t get enough credit for its creativity and ingenuity. I couldn’t agree more.

Whenever folks start to get snippy about how CBP and DHS are failing in some fundamental way to do this or that, I try to let them speak their piece, but then my protective nature kicks in. I am a customs lawyer, after all. These are my people! And I can think of no agency better suited to policing claims about global supply chains. Find me another government agency that has had the energy, creativity and ingenuity to, in a few short years, design and operationalize a law enforcement apparatus targeting a serious societal harm, and I’ll buy you some wasabi peas and Saratoga Springs mineral water.

But there’s a limit to what any government agency can do on its own, when it has no guiding statutory structure within which to operate. During the ACI event this week, I asked Brian Hoxie to predict some of the other areas where CBP might be called to enforce border restrictions against other ancillary ills of globalism and global trade (thinking of deforestation, carbon emissions, etc.). He properly demurred. CBP is a law enforcement agency, he said. They enforce the law. They don’t make the law.

CBP needs to be given a better legal structure to do what it’s been asked to do. I’ve made this point again and again in these pages, in public remarks, and in private discussion. Sometimes I debate with myself about whether CBP could close all the outstanding gaps and create it’s own rules-based structure with just some stellar agency rulemaking. But honestly, I think it’s just too much to ask.

Congress creates a statutory structure. The agency managing enforcement makes interpretive decisions and closes gaps with agency rulemaking. Then the agency runs the enforcement apparatus against the infinitely varied fact patterns of real world trade, becoming a true expert in the way that only an enforcer can, and rendering decisions in reference to the rules. Those decisions can be meaningfully and efficiently appealed to a neutral decisionmaker, because, everyone gets things wrong sometimes. And the rules allow for the identification and penalization of true bad actors, namely, trade cheats. That’s the model.

I’ll conclude with one final exchange, one that actually filled me with hope. In his remarks, Robert Silvers went on to say something that I have not heard any U.S. government official say to date. No one at CBP, no one else at DHS, no one from the CECC, no one on the China Select Committee, no one on the Hill, and no one in the Administration. He said: I know we have to get to the place where CBP can point to the problem that it sees in the supply chain, and an importer can look and see the same problem CBP is pointing at.

When I heard that, I thought: Robert Silvers gets it. And maybe he’s the only one in the entire U.S. government! If you’re a company that prioritizes trade compliance (a group that would include almost every public company or brand / importer whose name you would know), this is the whole point. This is all we’ve been asking for! Robert made clear that DHS operates (like we all do) within constraints. In this case, one of the real constraints are legal limitations around what CBP can disclose to an affected importer in the context of a law enforcement or trade enforcement operation. They’re working to solve that challenge. But knowing that they grasp the need is a very good sign.