Three Rules for Supply Chain Mapping

The George Strait Rule, the Captain Smith Canon, and Mapping for 6-Year-Olds

The single most important thing to grasp about U.S. forced labor import law is that:

the law imposes presumptions about labor, not origin.

Understand that, and everything else in the realm will be perfectly intelligible.

Well, perhaps I overstate. The inverse, however, is most definitely true: if you fail to understand that, nothing about forced labor trade enforcement will make sense.

Last post, I described how CBP sometimes improperly operates as if the law has authorized it to make presumptions about origin. This week, I direct our focus to the challenge that every importer facing a detention must solve—mapping the supply chain to show the UFLPA does not apply.

An importer whose goods are detained under the UFLPA will want to get them released. To do that, the best option available is to show that the detained goods weren’t manufactured wholly or in part in Xinjiang or by a UFLPA Listed Entity. If an importer can produce a map of the supply chain that identifies all the parties involved in the manufacture of the goods, across all stages of production, the Rubik’s Cube has been solved. If the mapped are outside of Xinjiang and not on the UFLPA Entity List, the shipment must be released.

But while the supply chain map is the most important tool in responding to any detention, the UFLPA provides no explicit guidance for companies that are now find themselves acting as a cartographer (or needing to hire one). Absent guidance from the law, I want to briefly offer views on three of challenging questions presented by supply chain mapping:

What constitutes a fatal flaw in a supply chain map?

Should an imperfect map ever be considered acceptable?

When to handicap based on mapmaking ability?

What Constitutes A Fatal Flaw in a supply chain map?

A supply chain map contains a fatal flaw when it asserts as true something that is demonstrably inaccurate. This simple standard of objective truth is elegant and irreplaceable, and applicable to all maps, not just supply chains. It should apply uniformly to anyone that purports to possess, sell, or have bought a supply chain map—importer, government agency, or tech platform.

The difficulty of mapmaking is no reason to accept inaccuracies. This may be a difficult truth when racing to cobble a supply chain map within 30 days of a detention. But it’s equally important as a standard for screening tech solutions.

Lots of tech platforms are looking to sell themselves as the Rand McNally of supply chain mapping. Any “supply chain map” that suggests the involvement of parties that are not actually involved in manufacturing goods wholly or in part isn’t worth its salt. Such a “map” cannot be relied on by an importer, and it should not be accepted by CBP, no matter its market share or branding.

Let’s call this the George Strait Rule. If a supply chain map shows oceanfront property in Arizona, don’t believe it.

Should an Imperfect Map Ever be Acceptable?

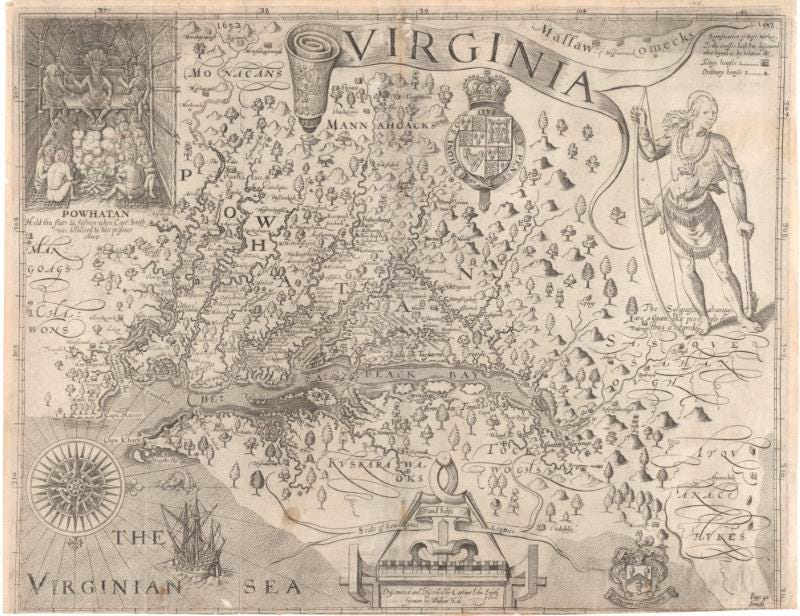

Sometimes there are close calls. A map might not contain outright inaccuracies, but may reflect distortions, or limitations of perspective. We’ll call this the Captain Smith Canon. When Captain Smith arrived in Virginia in 1608 and started sailing the estuaries of the mid-Atlantic, he produced this map:

Now, the Captain worked his tail off to make this . He spent nearly 4 years crafting it, before publishing in a pamphlet 1612. At that point, and for the next sixty years, it was the most accurate and detailed map of the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic coastline available in Europe.

It leaves something to be desired! It misconstrues the curvature of the Potomac, and improperly describes the width and length of the Eastern Shore. It somehow both compresses and truncates the Bay itself. Today we know that:

Nevertheless, it’s hard to argue that Captain Smith’s map isn’t a true and useful map. It was also an impressive feat, considering technological and resource constraints.

The point is, a map be a true and useful even when it elides certain details, because all maps elide details. That’s what makes a map a map. The least useful map in the world would contain all the detail of . . . the real world.

Provided a supply chain map does not violate the George Strait Rule, CBP should honor the Captain Smith Canon. Technological and resource constraints are not a reason to reject a map as worthless.

When to Handicap Based on Mapmaking Ability?

I recently asked my 6-year-old to make a map of our neighborhood, showing the route we take each day to school, and calling out some of her friends’ houses. Her response, I thought, was a fitting metaphor for the challenge of preparing a supply chain map as experienced by a small or medium-size enterprise.

First, she cried and said it was impossible. Then, with some prodding and encouragement, she agreed she could make a map, but insisted it would be a “treasure map”. Neighborhood unknowns (apparently there are many) would be marked with “X’s”. She grabbed some fluorescent paper, and a ballpoint pen, and returned in a half hour with “her map”. I told her it was extraordinary.

But reader, it was not. Yes, it showed an approximation of a “school”, and a girl on a bike, and a number of X’s. But they weren’t properly proportioned, let alone oriented, and there was no compass rose. I gave her a hug.

For small and medium size enterprises, the challenge of producing a complete and accurate supply chain map, showing the identity of every party that played a role in the manufacturing process, including of all components and raw materials, is a far different proposition for an SME than it is for the world’s most successful businesses.

It would be one thing if the UFLPA set an objective standard for supply chain mapping. For example, the law could have been drafted in such a way as to authorize CBP to detain any shipment from China, and then prescribe basic mapping parameters in order to “prove” the origin of the goods for customs purposes. But that it does not do. So, in the absence of that sort of guidance, when evaluating a mapping submission, CBP needs to exercise its discretion to give credit where credit is due.

What I’m Reading

Over the upcoming holiday weekend, I’ll be catching up on the UN’s report on human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Consider this my endorsement to do the same.

Thank you for reading! If you found this helpful, please feel free to share.

If you’ve happened upon this newsletter and are not yet a subscriber, sign up here. It’s free!